A significant effect of the coronavirus, and the measures that the Government has put in place to slow its spread, is that individuals’ incomes are experiencing significant damage. This is particularly true of individuals working in the tourism, hospitality, and leisure industries, and workers on zero hour contracts or in the gig economy. Such income loss impacts both the individuals concerned, and the level of demand in the economy, making a recession a significant risk.

An obvious suggestion to make is that a temporary Citizen’s Basic Income, or an equal one-off payment, should be paid to every individual legally resident in the UK. (Hong Kong recently made such a one-off payment to inject spending power into an economy affected by social unrest.)

Unfortunately, this option is not currently open to the UK, because there is no database that could be used for that purpose. There are lots of disconnected lists – driving licence holders, National Insurance numbers, National Health Service numbers, income tax references, passport holders, etc. – but no single list that contains names, contact details, and, crucially, bank account details, for every individual legally resident in the UK.

The coronavirus will not be the last such crisis, and we can envisage a variety of scenarios in which personal incomes will be rendered temporarily or permanently insecure, and in which spending power will therefore be reduced and the risk of recession increased.

As soon as the current crisis is over, a useful contingency plan would be to create a database containing the names, contact details, and bank account details for every legal resident, so that when the next crisis occurs the required mechanism will be available.

The British public has generally been averse to the Government constructing a single list of legal residents. When the last Labour government proposed issuing identity cards to every legal resident, the resulting public, media and political storm soon buried the plan. It is an interesting question as to whether a list of every legal resident’s name, contact details, and bank account details, designed for the positive purpose of paying a Citizen’s Basic Income or one-off payments, might be acceptable to public opinion.

To see Owen Jones’ article in The Guardian, click here.

… Yes, in the best of times, UBI would build a financial floor through which no citizen could fall below, and cement a decent standard of living in good times or bad for the precarious and self-employed. In a time of national emergency, it is surely a necessity …

Paul Spicker has written an article with a similar theme:

We have moved into lockdown, and the government has still given little thought to how to protect the situation of people on very low incomes. The main concessions relate to the failing system of Universal Credit: work allowances and benefit levels have been increased, the presumptive income of self-employed people no longer applies, and new sanctions have been suspended. Universal Credit is not, however, equipped to respond to people’s circumstances even in normal times, and it cannot cope with the surge in applications.

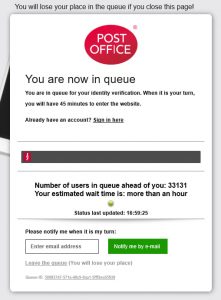

First, people have to apply.  This is a clip posted on Twitter by an applicant

This is a clip posted on Twitter by an applicant

What are the alternatives? There is a strong case being made currently for something like a Universal Basic Income. UBI only provides people with cash, but that meets the present situation: there are plentiful supplies of goods, and what we need to do at present is to make sure that people have the resources to buy them. I’ve objected to the idea in the past, mainly on two grounds: the distributive impact, which is likely to exclude people on existing benefits, and the opportunity cost. Neither of those reservations really applies to the present situation. The government could do worse than offering a flat rate payment to everyone.

However, the mechanisms to deliver a universal income don’t currently exist, and in a crisis, we need to be considering what can be done quickly and immediately. …

To read Paul Spicker’s article, click here.